Although Pablo Solomon is 65 years old, he isn’t ready for a life of retirement. You might find him canoodling with his wife Beverly in their spacious Texas ranch or creating stunning art and environmental design pieces that are celebrated internationally.

Before he achieved his life-long dream of creative and artistic freedom, Solomon joined the fight for the freedom and equality of blacks during the civil rights movement of the 1960s. During an era when blacks staged sit-ins in protest of unfair treatment and segregation, many believed that it was a case of black against white, but Solomon stepped across the line in support of equal treatment for all by working alongside those he felt had been treated unjustly.

“I was taught from childhood to judge people as individuals,” Solomon shares. “However, growing up in Texas in the time period that I did, there was segregation and even as a child I thought it was wrong.”

Solomon grew up in some of the poorest neighborhoods in Houston, Texas, where his family yearned to make it to a working-class neighborhood. His mother grew up picking cotton as a share cropper in south Texas, while his father’s family migrated from Lebanon to Mexico and then to Houston after fleeing devastating revolts.

By the time Solomon’s parents met, the differences in their background and cultures created the fertile ground, which helped Solomon to understand life on a level that takes the average person decades to reach.

The Beginning of a Shift

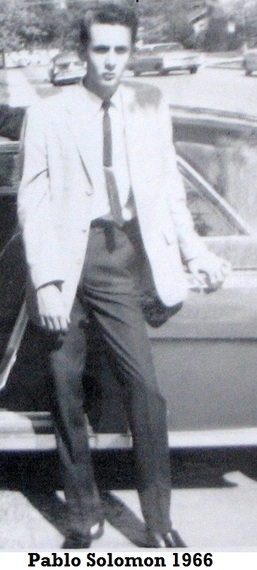

When the civil rights movement began, Solomon was a typical high school student sporting the unofficial uniform for kids of the day, jeans and a T-shirt. At his side he carried a “medicine bag,” which held a tiny Bible and a few special stones he had found, among other knick-knacks. Although Solomon swears he did not smoke dope like everyone else did, he does admit that a hot young lady could persuade him to smoke pot before engaging in more intimate activities.

As Solomon matured, so did the complexity of the various civil rights movements. Blacks were not the only group rallying for equality and fair treatment — farm workers, Hispanics, women and gay people were all standing up for themselves.

After receiving his teaching certification at the beginning of the move to integrate Houston schools, Solomon found himself assigned to schools that were in most cases, 98 percent black. Right before his eyes, Houston public schools embraced integration, a plan he says was botched from the very beginning.

“At first they were going to integrate one grade a year starting at first grade; however, this was overturned and all 12 grades were integrated at once which was a disaster from which public education still has not recovered,” Solomon says.

Solomon explains that before integration, black schools operated on an unofficial three-level system. Black students with potential were separated and pampered and motivated to be “better than the whites.” These were the students who went to college, became professionals and community leaders. The majority of students were given a barely adequate education and were kept in line by physical and often brutal punishments. They were motivated by sports and activities and a need to get jobs upon graduation. These were the blacks who would later work in industrial and retail jobs.

Then there were the lower caste of black students. Solomon says they were frankly encouraged to “get lost” and most did become lost in crime and drugs and prostitution. These students were not allowed to interfere with the education of the students that wanted to learn and the teachers ruled with a firm hand, backed by the most strict forms of corporal punishment.

Once the schools were integrated, everything changed. “All of a sudden the black schools had to cool corporal punishment and white teachers were just not prepared for the levels of disruption,” Solomon recalls. “All levels of students were thrown together and it was a mess. Add the epidemic of drugs at that time, and learning was near impossible.”

As Solomon released his staunch idealism, he was confronted by the reality of his own intentions and impact. By no stretch of the imagination was he anything like the iconic Sidney Poitier in the 1967 film To Sir, With Love, gliding in and charming his students into a new way of life. “I was sometimes brave, sometimes a coward, sometimes right and sometimes completely off base,” he says. “I was not a great teacher, but I tried.”

Vivid Images

The memories Solomon articulates are candid snapshots of an era that you won’t find in any history books. A tipping point for Solomon was Dr. King’s assassination. Having grown up in the South, he understood the resistance to change, yet witnessing a man who bravely tried to make the necessary and righteous changes murdered was just too much for Solomon. Immediately following Dr. King’s murder, violence erupted in numerous cities across the country.

“In a way, my motivation was as selfish as it was doing the right thing,” Solomon admits. “I did not want racial inequality to continue, nor did I want to be caught up in a violent race war.”

He painstakingly describes the most brutal battle that he ever witnessed: a three-way gang fight of about 100 Cubans, Mexicans and blacks. Teens, parents and cops fought vehemently, bashing each other with anything they could get their hands on outside of a school at the end of the day. There were no news stations called and no police enforcement to stop the melee. It was a complete free-for-all, a violent release of emotion.

During his tenure as a teacher during integration, Solomon bore witness to heinous acts directed toward staff members and students who were caught up in the angst of the times.

On one occasion a young black student at Solomon’s school threatened teachers and students with a knife. The student was merely removed and sent to another school, where he killed another student with his knife for not letting him cut in the lunch line.

Solomon hesitates as he recalls trying to console a white teacher who had been gang raped before school by black boys. She was told if she went to the cops, she would be fired. In response, Solomon organized a free self-defense class for teachers at the community college, which was later shut down because it gave the impression that the schools were dangerous environments for teachers.

At one point Solomon traveled a circuit of inner-city schools, helping teachers to improve their skills. Solomon remembers seeing Rev. Jesse Jackson visit one of the schools to offer his “I Am Somebody” speech.

“As corny as it may sound, it was great fun and truly motivational,” Solomon says. “For years, whenever I caught crap or was discouraged, I would think about the joyous pandemonium that Rev. Jackson got going and I just had to smile, hang in there and go on — I am somebody.”

Half-Hearted Reflections

Due to Solomon’s intense involvement in the civil rights era, he can’t romanticize his experiences like those reading it as an epilogue. Today Solomon says he is troubled that blacks and Hispanics have squandered the hard-earned rights and opportunities and are in many cases worse off than they were 50 years ago. “Sadly, I think more whites are over their racism than blacks are over their bitterness,” Solomon says.

Regardless of how much dirt he had to clean from under his fingernails in order to push a movement he feels has faltered in recent decades, Solomon says he does see a brighter future for our children and grandchildren. “With each generation there seems to be less ingrained racism and less bitterness and desire for revenge,” he says.

We may celebrate the heroes — the men and women who stood in the limelight, spoke eloquently and received mass applause for their leadership and dedication to racial equality — but Solomon is one of the few unknown men who stood against the majority when it was dangerous to do so, even though he had no idea if his efforts would reap rewards.

“I know that interesting stories of big events are what sells,” Solomon admits. “But the quiet truth is that this country made change one heart at a time.”

Originally Posted on The Huffington Post.